Is Germany building new coal plants to replace nuclear despite the country’s green ambitions? Many observers conclude so. But the growth of renewables has more than replaced nuclear power over the past decade. Coal is not making a comeback in Germany. However, German policymakers should reduce the country’s coal dependency sooner than scheduled.

The German Coal Conundrum: The status of coal power in Germany’s energy transition [PDF]

Germany has drawn international attention for its energy policies in recent years. The term Energiewende – the country’s transition away from nuclear power to renewables with lower energy consumption – is now commonly used in English.

The focus, however, has recently shifted to the role of coal in Germany. Over the last two years, media both in Germany and abroad have spoken of a possible “glowing future” for coal power and a “coal comeback” in Germany. From the decision to phase out nuclear power, observers conclude “that domestically produced lignite… is filling the gap”. Indeed, statements made by German politicians over the past decade also suggest that these coal plants were intentionally built to replace nuclear plants.

Here, we have the coal conundrum of the Energiewende: is Germany building new coal plants to replace nuclear despite the country’s green ambitions? This concern is based largely on a temporary uptick in coal power in 2012/13 (due to a cold winter and greater power exports) and on a round of new coal plants currently going online.

My colleagues Craig Morris, Thomas Gerke (graphics) and I have looked into this question in our new report The German Coal Conundrum [PDF]. It shows: coal is not making a comeback in Germany. The current addition of new coal projects in Germany is a one-off phenomenon. Recent projects started in 2005-2007 as part of an overall trend in Europe caused by low carbon prices and upcoming stricter pollution standards for coal plants. New coal plants in Germany are unrelated to the nuclear phaseout of 2011 after the Fukushima accident.

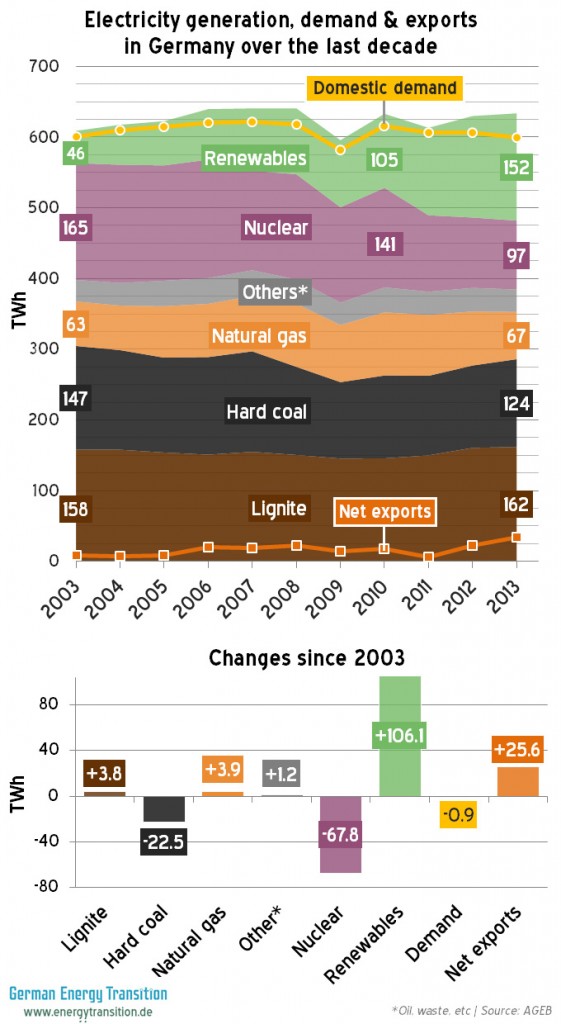

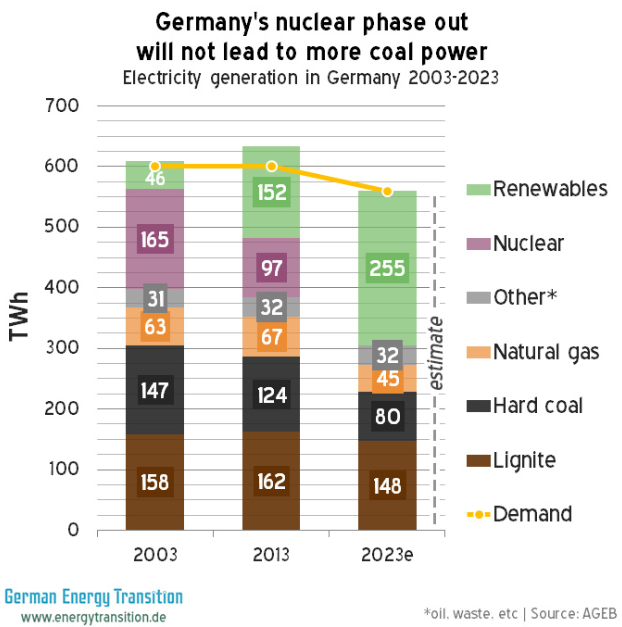

Instead, renewables have more than offset the shutdown of nuclear plants. Since 2003 (the start of the initial nuclear phaseout), electricity from nuclear dropped by 68 TWh. Over the same time, renewable electricity increased by 106 TWh. During the nuclear phaseout (completed by 2023), this trend can be expected to continue, though the specific outcome depends on the actual growth of renewables and demand for power in Germany and neighboring countries.

The crunch is on hard coal. Conventional power plants serve a shrinking “residual load” – a crucial term in understanding the German power sector – after the power demand covered by renewables. Less power will thus come from coal plants regardless of how many are built. Newly added capacity faces fewer operating hours. Given the surplus in power generation capacity, utilities are stopping new coal projects whenever they can.

Nonetheless, lignite is in a safe position during the nuclear phaseout unless policies are changed. Renewables have only slightly cut into demand for electricity from fossil fuel. Mainly, power from natural gas has been offset, with hard coal going next based on fuel price in the merit order. During the nuclear phaseout (until 2022), this situation can be expected to continue, though the specific outcome depends on the actual growth of renewables and demand for power in Germany and neighboring countries. Germany lacks specific policies to reduce lignite and increase natural gas use. Unless that changes, the market is unlikely to bring about a reduction in power production from lignite until the mid-2020s.

Germany can reduce its coal dependency sooner: Policymakers can – and should – implement policies to reduce Germany’s coal dependency before the mid-2020s: first and foremost by initiating a reform of the emissions trading system (EU-ETS). German policymakers should also consider taxing carbon and implementing a Climate Protection Act, focus more on efficiency, and strengthen natural gas as a bridge fuel. The EU is unlikely to find a consensus for ambitious policies anytime soon, so Germany should join forces with the large number of Member States willing to forge ahead. Here, the example set by the United States is illustrative; there, numerous communities, cities, and states have adopted their own climate and renewable energy targets rather than wait for policies from the federal level.

A coal phaseout could focus on removing the most polluting lignite plants in Germany. The United States has stricter emissions standards; if similar requirements were applied, Germany could begin switching off its biggest emitters of carbon as well.

Finally, Germany’s Energiewende proponents are not eager to correct the alleged but incorrect coal renaissance. There is a strong civil society movement in Germany which turns its efforts towards coal. Just this last week, 70 anti-coal activist from all over Germany gathered in Berlin for a capacity building and strategy workshop. The agenda is clear: coal needs to go down. Talks of a “coal comeback” are clearly overstated. But of course those activists are not rushing to correct such misreports. They need to keep up the pressure on policymakers to clamp down on coal consumption.

The report The German Coal Conundrum: The status of coal power in Germany’s energy transition was written by Arne Jungjohann and Craig Morris. Graphics by Thomas Gerke. Thanks to Rebecca Bertram and the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung North America to make this possible.

Pingback: Germany‘s dash for coal revisited | Arne Jungjohann

Pingback: A New Record: Renewables Make Up 78% of Germany’s Power Consumption in an Afternoon - Mebrat - Clean | Renewable Energy - Mebrat